CHAPTER XXII

My life in Sarawak • Chapter 30

CHAPTER XXII

One of my places of predilection in the country is called Lundu. It differs from most of the other settlements in Sarawak by the fact that a good deal of agriculture goes on in the neighbourhood, and that the country is flat near the Government Bungalow. We embarked for this place in the Aline, and although the water is shallow on the bar we managed to time our arrival at high tide, when the nine feet necessary to float our yacht enabled us to steer our way comfortably into the river, the banks of which are sandy at the mouth. Groves of talking trees grew close to the sea, and tufts of coarse grass were dotted over the sands. As we proceeded farther the soil became muddy and nipa palm forests appeared. We could see the mountain of Poe, three thousand feet in height, towering inland. It is one of the frontiers between the Dutch country and Sarawak, so that the Rajah and the Dutch Government each possess half of this mountain. It is not so precipitous as is Santubong, and has forest trees growing thickly right up to the top. Fishing stakes were stretched across some of the sandbanks at the mouth, but not a living soul was to be seen on the sea-shore. We steamed through a broad morass, crossed in every direction by little streams travelling down to the main river. Farther on we noticed, about twenty or thirty yards from the banks, a tree full of yellow blossoms, like a flaming torch in the green gloom of the jungle. No one could tell me what these blossoms were, and I was deeply disappointed at our inability to reach the tree and obtain some of its branches, which might as yet be unknown to science. It would have taken our sailors many hours to hew their way to it, so we contented ourselves with looking through opera glasses, across a jungle of vegetation, at the gorgeous blossoms, although that did not help us to discover what the tree was.[11] A little farther on were huts built near the river, and we could see men sitting on the rungs of ladders leading from their open doors to the water.

When we arrived at Lundu, our friend Mr. Bloomfield Douglas, Resident of the place and living in the comfortable Government bungalow situated a few yards from the river, came to meet us at the wharf, accompanied by a number of Dyaks. A Dyak chief styled the Orang Kaya Stia Rajah, with his wife and relations, came on board with Mr. Douglas to take us on shore. Both men and women wore the conical hats of the country, made of the finest straw. A piece of light wood delicately carved to a point ornamented their tops, which were made splendid with bright colours. My old friends, the Dyak women, were affectionate and kind. They took hold of my hand, sniffed at it, and laid it gently back by my side; some of the Dyak men followed suit. These people never kiss in European fashion, but smell at the object of their affection or reverence. I always felt on such occasions as though two little holes were placed on the back of my hand.

On the day of our arrival, the sun was blazing overhead and it was fearfully hot. Our shadows were very short as we moved along, and the people lined the way right up to the Resident’s door. We had to touch everybody individually as we marched along, even babies in arms had their little hands held out to touch our fingers. These greetings took some time in the overpowering heat of midday, and it was a great relief when at last we reached Mr. Douglas’s pretty room, which he had been wise enough to leave unpainted and unpapered. The walls were made of the brown wood of the country, and were decorated with hanging baskets of orchids in full flower, vandalowis, philaenopsis, etc.—a mass of brown, yellow, pink, white, and mauve blooms, hanging in fragile and delicate cascades of colour against the dark background. Rare and wonderful pots of ferns were placed in my bedroom, and quantities of roses, gardenias, jasmine, and chimpakas scented the whole place.

In the evening we took a walk round the settlement. The many plantations of Liberian coffee trees looked beautiful weighed down with green and scarlet berries, some branches still retaining their snowy blossoms. The contrast of berries and flowers, with the glossy dark green of the leaves, made them a charming picture in the landscape. We went through fields planted with tapioca and sugar-cane, and across plantations of pepper vines. These latter are graceful things, trained up poles, with small green bunches hanging down like miniature clusters of green and red grapes. In every corner or twist of the road we met little groups of men and women waiting for us. They stood in the ditches by the side of the paths until we came up to them, when they jumped out, rushed at us, sniffed at the backs of our hands, and retired once more to the ditches without saying a word.

During the night I heard the Argus pheasant crying in the woods, in response to distant thunder. These beautiful birds roam about the hill of Gading, which is close by the bungalow and thickly covered with virgin forest. The sound they make is uncanny and sorrowful, like the cry of lost souls wandering in the sombre wilderness of innumerable trees, seeking to fathom the secrets of an implacable world. Any sudden loud sound, as of a dead tree falling or the rumble of thunder, however remote, apparently calls forth an echo of terror from these birds.

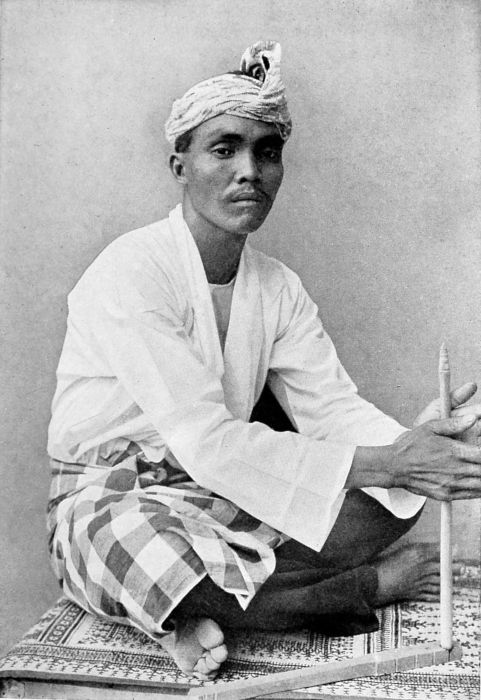

The next evening the chief of the village invited us to a reception at his house, situated a short distance from the bungalow. It was a fine starlight night, and we walked there after dinner. The house was built much in the same way as are other Sea Dyak houses, the flooring being propped on innumerable poles about thirty feet from the ground. A broad verandah led into the living-rooms, but, as usual, we had to climb a slender pole with notches all the way up, leaning at a steep angle against the verandah. The chief, with an air of pomp and majesty, helped me up the narrow way as though it were the stairway of a palace. His manner was courtly and his costume magnificent. His jacket and trousers were braided with gold, and the sarong round his waist was fastened with a belt of beaten gold.

The house was full of people: Dyaks who had come from far and near, Chinamen resident in the place, Malays from over the Dutch border, and even a few Hindoos, or Klings, were to be seen. The chief took us to the place prepared for us at the end of the verandah, where was hung a canopy of golden embroideries and stiff brocades. Branches of sugar-canes and the fronds of betel-nut palms decorated the poles of the verandah. A great many lighted lamps hung from the roof, and the floor was covered with fine white mats. Bertram, Mr. Douglas, Dr. Langmore, and I sat on chairs, whilst the rest of the guests squatted on mats laid on the floor.

The women and young girls sat near me, one of the latter, whose name was Madu (meaning honey), being very pretty indeed. Her petticoat of coarse dark cotton was narrow and hardly reached her knees, and over this she wore a dark blue cotton jacket, fastened at the neck with gold buttons as big as small saucers. Her eyes were dark, beautiful and keenly intelligent, and her straight eyebrows drooped a little at the outer corners. The high cheek-bones, characteristic of her race, gave her a certain air of refinement and delicacy, in spite of her nose being flat, her nostrils broad, and her lips wide and somewhat thick. Her hair was pulled tightly off her forehead, and lay in a coil at the nape of her neck; it seemed too heavy for her, and as she carried her head very high, the great mass looked as though it dragged it backwards. Her hair, however, had one peculiarity (a peculiarity I had never seen in Sarawak before); it was streaked with red, and this made Madu unhappy, for Malays and Dyaks do not like the slightest appearance of red hair, some of the tribes shaving their children’s heads from early infancy until they are seven years old, in order to avoid the possibility of such an occurrence. The little creature looked pathetic, as she sat nursing her sister’s baby, around whose wrist was tied a black wooden rattle, like a small cannon-ball. The baby was about two months old, and appeared to be healthy, but a sudden kick on its part removed a piece of calico, its only article of clothing, when I saw that the child’s stomach had been rubbed over with turmeric, to prevent it from being seized by the demon of disease. The chief told his daughter to leave the child to its nurse, when a very old lady rushed forward and took it away.

Refreshments were then handed round. We had glasses of cocoa-nut milk, cakes made of grated cocoa-nut and of rice flour, intensely sweet. There were large trays of pumeloes, cut in quarters, together with oranges, bananas, and mangosteens. Glasses of gin, much diluted with water, were handed to the male guests, and after refreshments a place was cleared right down the room, the chief’s native friends sitting on mats on the floor, leaning against the walls.

The orchestra was placed on one side of the hall. It consisted of a set of gongs, called the Kromang, seven or eight in number, decreasing in size, fixed in a wooden frame, each gong sounding a different note—a scale, in fact. These gongs are beaten by one individual, and when skilfully played they sound like running water. Other members of the orchestra played gongs hung singly on poles, and there were also drums beaten at both ends with the musician’s fingers. These instruments played in concert and with remarkable rhythm were pleasant to listen to. When the band had finished the overture, two young men got up after an immense amount of persuasion, and walked shyly to the middle of the cleared space. They were dressed in Malay clothes—trousers, jackets, and sarongs—and smoking-caps, ornamented with tassels, were placed on one side of their heads. They fell down suddenly in front of us, their hands clasped above their heads, and bowed till their foreheads touched the floor. Then they got up slowly, looked at one another, giggled, and walked away. The master of the house explained that they were shy, and thought their conduct quite natural. It was evidently the thing to do, for several other couples went through this same pantomime. At last the first couple were induced to come back, when their shyness vanished, and the performance began.

One of the dancers held two flat pieces of wood in each hand, clicking them together like castanets. The other man danced with china saucers held in each hand, keeping time to the orchestra by hitting the saucers with rings of gold which he wore on each forefinger. He was as skilful as any juggler I had seen, for he twisted the saucers round and round, his rings hitting against them in time to the music with wonderful accuracy. The dancers were never still for a second. Their arms waved about, their bodies swayed to and fro, they knelt first on one knee with the other leg outstretched before them, then on the other, sometimes bending their bodies in a line with the floor—the castanets and the saucers being kept going the whole time. Although the movements looked stiff, it was impossible for them to be ungraceful, and at every new pose they managed to fall into a delightful arrangement of lines. The dances were evidently inspired by Malay artists, although performed by Dyaks, for they were full of restraint.

Other dances followed, all interesting and pretty. Sometimes empty cocoa-nut shells, cut in two, were placed in patterns on the floor. The dancers picked up one in each hand, clashing them together like cymbals, whilst hopping in and out of the other cocoa-nuts, this performance being called by the people “the mouse-deer dance,” for they imagine that the noise made by clashing the cocoa-nut shells resembles the cry of plandoks (mouse-deer) in the forests.

After the men had finished, the women’s turn came. These wore stiff petticoats of gold brocade, hanging from under their armpits and reaching almost to the floor, under which were dark blue cotton draperies hiding their feet. The pretty Madu, with the red-streaked hair, headed a procession of about thirty young women and girls, who emerged from the open doorway at the other end of the room, in single file. They stretched out their arms in a line with their shoulders, and waved their hands slowly from the wrists. Their sleeves were open and hung from the elbow weighted with rows upon rows of golden knobs. With their heads on one side and their eyes cast down, they looked as though they were crucified against invisible crosses, and wafted down the middle of the hall. When they approached us, they swayed their bodies to right and left and extended their arms, beating the air gently with their hands, keeping exactly in line, and followed Madu’s gestures so accurately that from where I stood I could only see Madu as she headed the dancers. It would be interesting to know the origin of such dances. I imagine the Hindoo element pervades them all. How surprised these so-called savages would be if they were present at some ballet, with women in tights and short stiff skirts, kicking their legs about, or pirouetting on one toe, for these natives are innately artistic, if kept away from the influence of European art and its execrable taste. Each time a movement more graceful than the last was accomplished by these young women, the men evinced their approbation by opening their mouths and yelling, without showing any other signs of excitement on their immovable faces.

The dances went on for some time, after which wrestling matches took place between little boys of the tribe, about eleven or twelve years of age. When one of these small wrestlers was defeated he never showed bad temper or appeared maliciously disposed towards his conqueror.

We all enjoyed ourselves, and it was late when we left this hospitable house. The chief and his daughters offered us more cocoa-nut milk, cakes, and bananas, and the leave-taking took some time. One old Sea Dyak, who had been very conspicuous during the evening, for he had bounded about and joined in the dances, took my hand and put it into the hand of a friend of his, another Sea Dyak, whom he particularly wished me to notice. “You make friends,” he said, “for my friends are your friends.” I hope I responded sympathetically, and after a while we managed to drag ourselves away.

Our hosts escorted us back to Mr. Douglas’s bungalow. I led the way, hand in hand with the chief, and Bertram followed, hand in hand with the chief’s son, who kept assuring Bertram that he felt very happy, because they had become brothers, for was not Rajah Ranee, his mother, walking home hand in hand with his father, and as he was doing the same with her son, that quite settled the relationship. The orchestra followed us the whole way home, and the people sang choruses to impromptu words, composed in our honour by the poet of the tribe. The chief told me the song was “manah” (beautiful), as its words were in honour of Bertram and me.

A recent shower had left the night fine and the air cool, as we went through avenues of betel-nut palms and over carpets of lemon grass, whose long spikes beaten over the path by the rain gave a delightful fragrance crushed by so many feet. We crossed a little bridge over a bubbling stream, and passed by Chinese houses, whose inhabitants opened their windows to look at our midnight procession. When we reached the bungalow, the arbor tristis or night-flowering jasmine was in bloom all over the garden, and white moon-flower bells hung wide open over the verandah. Half an hour later, as I leaned out of the window of my bedroom, I could still hear the people singing on their way back to the village. The trees in the garden were full of fireflies looking like stars entangled in the branches.

We left Lundu the next day with regret. We were sorry to say good-bye to our kind host, Mr. Douglas, and to the Dyaks of the place, and as we steamed away I felt almost inclined to cry. Although I may be accused of being unduly emotional, I am not ashamed to own that after a visit in any of the Sarawak settlements I always left a piece of my heart behind.

FOOTNOTES:

[11] This tree, which no one could tell me the name of at the time, was the only one of its kind I had seen; therefore, it was not strange I formed the idea it might be unknown to science. Its leafy image persisted in my mind, and the thought of it haunted me. I have now been informed that it is not unknown, and is a creeper, called Bauhinea, and not a tree at all. Seen at a distance, its appearance is like that of a tree in blossom, for it completely covers—and perhaps smothers—the tree upon which it fastens itself.