CHAPTER XXIX

My life in Sarawak • Chapter 37

CHAPTER XXIX

During our stay at Simanggang I saw, as usual, a great many natives, and being interested in the legends of the place, I persuaded my visitors to relate some of these to me. It should be remembered that none of these legends have been written down by themselves, since the Dyaks possess no literature, with the result that they vary in the telling. I cannot say positively that the following legends have not already appeared in print; to my mind, however, their interest lies in their slight difference; every variation goes to show how strongly these legends are embedded in the minds and lives of the people, and should, in their way, help to unfold the secret of their origin.

I found that the strange idea of people becoming petrified by storms and tempests, through laughing or ill-treating animals, was universal amongst the inhabitants of this district. The following are two stories regarding this belief, told me by my friends.

Many years ago there was a little village called Marup, far up the Batang Lupar River. It stood on the banks near its source, and below the village the water rippled over pebbles under the shade of great trees. There were deep pools here and there between the rocks, where fish could be seen swimming about, and these the village boys caught in their hands. It was a happy little place, too poor to be attacked by robbers, and out of the reach of the terrible head-hunters living nearer the coast. The orchards round the village were full of fruit, and the rice-crops were never known to fail. The women passed their time weaving cloths made from the cotton growing on the trees round their dwellings, or working in the rice-fields, whilst the men fished, hunted, or went long journeys in their canoes in search of certain palms, which they brought home to their women, who worked them into mats or plaited them into baskets. One day a young girl went down to the river with her net. She filled her basket with fish called by the people “Ikan Pasit.” The girl took them home, and as she was preparing them for supper, the smallest fish jumped out of the cooking pot and touched her breast. “What are you doing?” she said to the fish. “Do you imagine that you are my husband?” and at this joke she laughed heartily. The people who were watching her prepare the meal joined in the laugh, and the peals of laughter were so loud that the villagers, hearing the noise, rushed to see what was the matter, and they too began to laugh. Suddenly, a great black pall was seen to rise over the western hills, and spread over the sky. A mighty wind blew accompanied by flashes of lightning and detonations sounding like the fall of great hills. Then a stone-rain (hail-storm) began, and soon a terrible tempest was in progress. The torrents of rain and hail were so dense that day turned to night. After a time the rain ceased, but great hailstones beat pitilessly down on the village until every man, woman, and child, and every animal, even the houses themselves, were turned to stone and fell into the river with a loud crash. When the storm subsided, a deep silence lay over the valley, and the only traces of that once happy settlement were great boulders of rock lying in the bed of the stream.

The girl who had been the first to mock at the fish was only partly petrified, for her head and neck remained human and unchanged. She, also, had fallen into the river, and was embedded like a rock in the middle of the stream. Thus she lived for many years, with a living head and neck, and a body of stone. Whenever a canoe paddled by she implored its inmates to take their swords and kill her, but they could make no impression whatever on her stone body or on her living head. They could not move the rock, for it was too big, and although they hacked at her head with axes, swords, and various other implements, she bore a charmed life, and was doomed to remain alive. One evening a man paddled by, carrying his wife’s spindle in the bottom of his canoe. He heard the girl’s cries, and tried all means possible with his axe and his sword to put her out of her misery; at length in a fit of impotent despair he seized hold of the spindle and struck her over the head with it. Suddenly her cries ceased, and her head and neck slowly turned to stone. This legend is known to a great many of the Dyaks living up the Batang Lupar River, and the group of rocks was pointed out to me when we passed by them, if I remember rightly, not far from Lobok Antu.

The other legend is known as the Cat story, and is supposed to have happened to a tribe who lived not far from the lady turned to stone by a spindle. This village was also built on the banks of one of the little streams flowing into the Batang Lupar River. The chief was a proud, haughty man, whose tribe numbered one thousand men, women, and children. He was given the title of “Torrent of Blood,” whilst his more famous warriors were also distinguished by similarly splendid names. His house was so large that it had seventy-eight doors (meaning seventy-eight families lived under the same long roof). He was indeed a great man: when he consulted the birds, they were favourable to his wishes, and when he led his warriors to battle, he always returned victorious, with his boats laden with heads, jars, sacks of paddy, and plunder of various kinds. No tribe in Borneo could equal the noise made by his warriors when they gave vent to the terrible head yells, by which they made known to the countryside that they were returning from some successful expedition. Practice had made them perfect, and the mountains, rocks, and valleys resounded with their shouts. When an expedition returned, the women and children stood on the banks to watch the arrival of the boats. The most distinguished warriors’ helmets were decorated with hornbill’s plumes, and their war-jackets were a mass of feathers. None but renowned head-hunters were allowed to wear the hornbill’s plumes, for they were a token of the wearer having captured heads of enemies in battle.

But there was one poor individual who could take no part in either these warlike expeditions, or in the “Begawai Antu” (head feast) given in honour of heads of enemies taken in their wars. Some years before, the poor man’s parents had accidentally set fire to one of the houses in the village, and, according to the custom of these Dyaks, such a misfortune entailed the whole of the culprit’s family being enslaved. One by one the relations of the poor man had died, until he remained the only slave of the tribe. Indignities were heaped upon him, he was looked upon with great contempt, and made to live in the last room of the village where the refuse was thrown. One day, feeling more desolate than usual, he made friends with a cat belonging to the tribe. He enticed the animal into his miserable room and dressed it up in a scarlet waistband, a war-jacket made of panther’s skin, and a cap decorated with hornbill’s plumes: in short, in the costume of a distinguished Dyak warrior. He carried the animal to the open verandah in sight of the chiefs and elders who were discussing plans for a fresh expedition, and of the women and young girls husking the paddy. There, before them all, the friendless creature hugged the cat and held it to his heart. He was nearly weeping and tears stood in his eyes, but hard-hearted and scornful, the people pointed at him in derision for owning such a friend, and laughed loudly. The warriors forgot about their war plans and the women about their paddy, in their keen enjoyment of the poor man’s misery. Suddenly, he let the cat jump out of his arms, and as it touched the ground it ran like a mad thing in and out of the crowd, dropping here and there the cap, the jacket, and the scarlet waistband. Freed from these trappings, the cat leapt out of the house and disappeared. Then a great storm arose and the stone-rain fell upon the people. The chief of the village, together with all his tribe, were hurled by Antu Ribut into the stream, and they and their houses were turned into those great rocks which anyone can see for himself if he will take the trouble involved in a journey up those many reaches of the Batang Lupar River. The poor despised man found rest and shelter in the general confusion, for he crept inside a bamboo growing near the house, and there he has remained ever since, embedded in its heart.

Dr. Hose has told me that Bukitans and Ukits also believe in the danger of laughing at animals, for he once had a baby maias[13] which learnt to put its arms into the sleeves of a small coat, until it quite got to like the coat. When visiting Dr. Hose at the Fort these people sometimes saw the creature slowly putting on his coat, when they hid their faces and turned away their heads, for fear the animal should see them laughing at it. When Dr. Hose asked them why they were afraid to be seen laughing, they replied, “It is ‘mali’ (forbidden) to laugh at an animal, and might cause a tempest.”

Here is another legend about people being turned to stone on account of ingratitude and disrespect to their parents. Not far from the mouth of the Batang Lupar River, some miles up the coast, are rocks standing on the shore and which, according to my friends, were remains of an ancient village, in which a man, his wife, and their son once lived. The parents were exceedingly fond of the boy and brought him up with especial care. The father taught him how to make schooners, how to fashion canoes, and to make nets in order to obtain a large haul of fish: indeed, he taught the boy all he knew. When the lad grew up, he started from his village on a trading expedition in a schooner built by his father and himself. The parents parted regretfully with their child, but in their unselfishness they were only too glad he should go forth in the world outside their little settlement and make a name for himself. After many years the son managed to amass a considerable fortune from his trading expeditions, and returned to the place of his birth to visit his father and mother who had never for a moment forgotten the boy so dear to them. But, so the story goes, when he realized the poverty of their surroundings and their position in the world, his heart grew hard towards them, and he felt ashamed of their low estate. He spoke unkind words to the old couple, who had almost given their life’s blood to build up his fortune. One day, after insulting them more than usual, a great storm arose, and father, mother, and son, together with the whole of the inhabitants of the village and their houses, were tossed into the sea and turned into stone.

The Batang Lupar district is rich in legends, and I will tell yet another as related to me by a fortman’s wife in Simanggang. Every one living in Simanggang knows the great mass of sandstone and forest, called Lingga Mountain, and all those who have travelled at all (so said the fortman’s wife) have seen this Lingga Mountain and know how high and difficult it is to climb, and how a great stretch of country can be seen from its flat and narrow top with the wide expanse of sea stretching from the shores of the Batang Lupar across the great bay of Sarawak to the mountains beyond the town of Kuching. A young Dyak, named Laja, once resided in a village at the foot of this mountain. A beautiful lady, the Spirit of the mountain, one night appeared to him in his dreams, and told him he must rise early the next morning, before the trees on the banks of the river had emerged from the mists of night, and climb Lingga Mountain, where he would find the safflower (that blossom which has since become so great a blessing to the Dyak race) at the top. The vision went on to explain that this plant would benefit Laja’s tribe, for it could cure most illnesses, more especially sprains and internal inflammation. Laja obeyed the orders of this beautiful lady and started off the next morning before dawn had broken over the land. He had climbed half-way up the mountain when he saw, just above the fog, the fragment of a rainbow, like a gigantic orchid painted in the sky, its rose colour gleaming through the mist and melting away in the most wonderful moss-green hue. Seeing the coloured fragment, Laja knew at once that the Spirit of the mountain, a king’s daughter, was about to descend by the rainbow to bathe in the mountain stream. When the colours had faded from the sky, Laja went his way, until he reached the top, where he had some difficulty in finding the safflower on account of its diminutive size. After searching for some time, he found the root and carried it back to his village. He then pounded it up and gave it to people who were sick. But the plant was capricious, for, whilst it cured some, others derived no benefit from it and died. Its successes, however, proved more numerous than its failures, and every member of the tribe became anxious to procure a root for himself, although no one ventured to undertake the journey at the time as the farming season was in full swing, necessitating the villagers working hard at their paddy; moreover, the place where the plant grew was a long way off and the climb up the mountain was a somewhat perilous one.

Notwithstanding, a young man, named Simpurei, started off one day in search of the safflower, without telling anyone of his intentions. When he reached half-way up the mountain he saw the rainbow glittering in the sky, but instead of its being a fragment, its arch was perfect, both ends resting on the sides of a hill opposite the mountain. Simpurei realized that the king’s daughter must be bathing in the neighbourhood; nevertheless, he still went on. He heard the sound of water and rustling leaves close by, and, pushing aside a great branch of foliage, peered through, when he saw a woman most divinely beautiful bathing in a pool. She was unclothed, her hair falling down her back until it touched her feet. She threw the water over her head from a bucket of pure gold, and as Simpurei stood staring at this beautiful vision, one of the twigs in his hand broke off. At the sound the girl looked up, and seeing the youth, fled to a great bed of safflowers near which her clothes were lying. As she sped away, one of her hairs became entangled in the bushes and was left hanging there. Simpurei saw it all wet and glistening, like a cobweb left on a branch after a dewy night, and rolling the fragile thread up carefully, put it with the beads, pebbles, pieces of wood, seeds, etc., which he carried about with him as charms, in his sirih bag.

He hastened home, having forgotten the safflower in the excitement of this unexpected meeting, but he had scarcely reached his house when he was seized with violent illness. He lingered for some hours, for he had time before he died to relate his adventures to the whole of the village who had immediately come to his house on hearing of his illness. Medicine men were called in, but their remedies were of no avail, and the elders of the tribe showed their wisdom when they decided that his death was a just punishment sent him by the Rajah, the Spirit of the Sun:—for had not Simpurei stood and gazed at his daughter when she was unclothed?

Another legend, which I had from the fortman’s wife, telling how the paddy was first brought to Borneo, is a general one all over the country, and is related by many of our people with certain variations. Some generations ago a man dwelt alone by the side of a river in a small hut. One day, after a succession of thunder-storms and heavy rains, he was watching snags and driftwood hurrying down the stream after heavy freshets, owing to which the upper districts of the river had been submerged and a number of people drowned in the flood. A snag, on which perched a milk-white paddy bird, was hurrying to the sea, followed, more leisurely, by a great tree torn up by its roots. This tree got caught in a sandbank and swung to and fro in the current with a portion of its roots above water. The man noticed a strange-looking plant entangled in its roots, and unfastening his canoe from the landing-place near by, he paddled to the spot and took the plant home. It was a delicate-looking thing with leaves of the tenderest green, but thinking it of no use, he threw it in a corner of his hut and soon forgot all about it. When evening came on he unfolded his mat, put up his mosquito-net, and was soon fast asleep. In his dreams, a beautiful being appeared to him and spoke about the plant. This phantom, who seemed more like a spirit than a man, revealed to him that the plant was necessary to the human race, but that it must be watched and cherished, and planted when seven stars were shining together in the sky just before dawn. The man then woke up and, pulling his curtains aside, saw the plant lying in the corner of the hut shrivelled and brown. There he left it, and went to visit a friend living in the neighbourhood, to whom he related what had happened, and went on to say that the spirit of his dreams must be very stupid in telling him to look for seven stars when there were always so many shining in the sky. But his friend was a wise man and able to explain the meaning of his dream. He told him that Patara himself had appeared to him, and that the seven stars were quite different from other stars, as they did not twinkle, but remained still in the heavens, and as they chose their own season for appearing in the sky no one could tell for certain, without their help, when the new plant was to be put in the ground. The friend, being also versed in the law of antus, or spirits, said that the plant found in the roots of the tree was paddy (rice), and that Patara had taken the trouble to say so himself.

After this explanation the man went home, picked up the plant and put it away carefully until another dream should reveal when he was to look out for the seven stars. In due time, under Patara’s guidance, the man noticed the “necklace of Pleiades” appearing in the sky. The little plant was then put in the ground, where it grew and multiplied. The people in neighbouring villages also procured roots to plant in their farms, so that the paddy now flourishes all over the country and the people of Sarawak have always enough to eat.

Sarawak people have very beautiful ideas about paddy, and their mythical tales about the food-giving plant remind one of the many legends all over the world relating to Demeter and other earth-mother goddesses. Amongst some tribes, indeed, I fancy, nearly all over Sarawak, the people plant the roots of a lily called Indu Padi (or wife of the Paddy, by Sea Dyaks) in their paddy fields. They treat this flower as though it were the most powerful goddess, and every paddy field belonging to the Dyaks of the Rejang, of the Batang Lupar, of the Sadong, and also of the Land Dyaks near Kuching, possesses a root of this flower.[14] They build little protecting huts over it, and treat its delicate and short life with the utmost care and reverence. I have often tried to get a glimpse of this flower, but have never succeeded. However, a good many of the Rajah’s officers, who have lived some time in native houses, and who have witnessed the people’s harvest festivals, have given me a description of it. I have always thought it such a beautiful superstition of theirs that of caring for and nurturing the delicate petals of a flower as though its fragile existence were a protection to the well-being of their race. They greatly fear anything happening to the plant, for should it die or shrivel up before the paddy is husked and garnered, it is thought to bode disaster to their tribe.

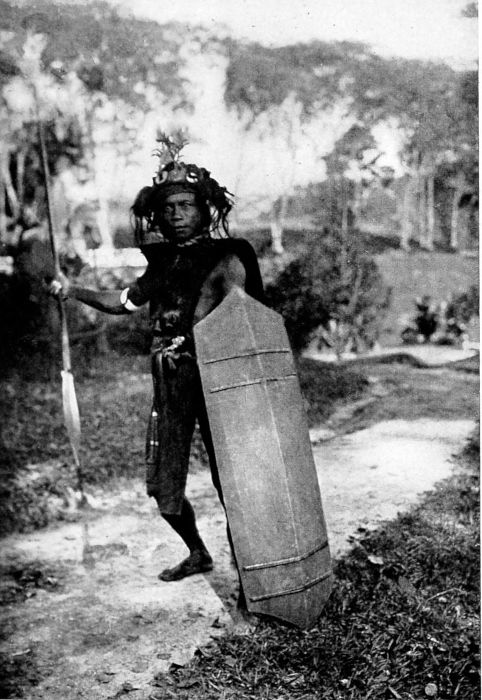

A chief named Panau, who had a considerable following, often paid me visits in our bungalow at Simanggang. I had known him for years, and, like all Dyaks, he was fond of talking, and a shrewd observer of men and things. He was a reader of character, and when he trusted anyone became their loyal friend. His dark, restless eyes, his smiling face, his swagger, his conceit, his humility, and his kindness always interested me. He had a sense of humour, too, and cracked many jokes of which I did not always catch the sense; this was perhaps fortunate, as Dyak jokes are sometimes Rabelaisian in character. He was greatly interested in my camera, and thought the manner in which I fired at the landscape and caught it in the box nothing short of miraculous. One day I took his portrait, attired in his war-dress. He kept me waiting for some minutes adjusting a warlike pose before I pulled off the cap. “Let those who look upon my picture tremble with fear,” he said, as he grasped his spear in one hand and his shield in the other. I took him into the dark room arranged for me in our bungalow to see me develop the picture. He looked over my shoulder as I moved the acid over the plate, and when he saw his likeness appear, he gave a yell, screamed out “Antu!” tore open the door, and rushed out, slamming the door behind him. On that account his picture is somewhat fogged. It took some time before he recovered from his fright, but he eventually accepted one of the prints. A great reason I had for enjoying Panau’s company was his devotion to my eldest son, Vyner, who had visited Sarawak the previous year. At the time of Bertram’s and my stay in Sarawak, Vyner was finishing his education at Cambridge. Panau confided to me that he longed for the time to come when his Rajah Muda would be amongst his people again. It appeared that Vyner had made many peaceful expeditions up the Batang Lupar River with Panau and his tribe. On one occasion Panau informed me he had saved Vyner from being engulfed by the Bore. When, on my return to England, I asked Vyner for details, he told me he did not remember the incident, and thought it must have existed only in Panau’s imagination. I daresay Panau, having so often related this imaginary adventure, had come to look upon it as true. At any rate, the Chief was devoted to him, and, knowing how deeply my eldest son appreciates the natives, it was pleasant to realize how much he was esteemed by them in return.

I do not think it would be amiss to relate in this connection a subsequent adventure that befell Vyner some years after my stay at the Batang Lupar River, up one of its tributaries. The Rajah found himself obliged to send an expedition against a tribe who had committed many murders in these inland rivers. The expedition started from Simanggang, with Mr. Harry Deshon in charge of a force of Dyaks and Malays numbering about eight thousand, whilst Mr. Bailey and Vyner accompanied them. For some unexplained reason, cholera broke out amongst the force just before it had reached the enemy’s country. It was impossible to turn back on account of the bad impression such a course would have made on the enemy, so that, in spite of losing men daily, the expedition had to push on. When the force reached the enemy’s country, a land party was dispatched to the scene of action. A chosen body of men, led by Malay chiefs, started on foot for the interior, leaving the Englishmen and the body of the force to await their return. During those days of waiting, the epidemic became most virulent. The three white men had encamped on a gravel bed, and the Dyak force remained in their boats close by. As the days wore on, the air was filled with the screams and groans of the stricken and dying. Out of six or seven thousand men who remained encamped by the shores of the river, about two thousand died of the plague, and to Vyner’s great grief and mine our old friend Panau was attacked with the disease, and died in a few hours.

Mr. Deshon and Mr. Bailey have since told me that Vyner’s presence helped to keep discipline and hope amongst the force during the awful time. He was always cheerful, they said. It appears that Vyner and his two friends used to sit on the gravel bed and with a grim humour point out to one another where they would like to be buried, in case at any moment they might be carried off by the plague.

When, after having conquered the head-hunters, the attacking party returned to camp, they found the gravel bed strewn with the bodies of the dead and dying. The return journey to Simanggang was terrible, for all along those many miles of water, corpses had to be flung from the boats in such numbers that there was nothing to be done but to leave them floating in the stream. The enemy, subsequently hearing about the catastrophe, hurried to the place where the Rajah’s force had been encamped, and finding there so many dead bodies, proceeded to cut off their heads and to carry them home. These people, however, fell victims to their detestable habit, for they caught the cholera and spread it amongst their tribe, with the result that it was almost annihilated. A great stretch of country became infected, and the little paths around Simanggang were littered with the corpses of Chinese, Dyaks, and Malays. Nothing apparently could be done to stop the disease, which disappeared as suddenly as it had come, but this calamitous epidemic destroyed nearly one-quarter of the population.

Happening to be in Italy at the time, I read in an Italian paper that the Rajah’s son had died of cholera in Sarawak, as he was leading an expedition into the interior. I hurried to England with my younger son, Harry, who was staying with me at the time, and when we arrived at Dover, placards at the station confirmed the report. Telegrams, however, soon put us out of suspense, but I had spent a terrible day.